Binding bad: Buckyballs offer environmental benefits

Treated buckyballs not only remove valuable but potentially toxic metal particles from water and other liquids, but also reserve them for future use, according to scientists at Rice University.

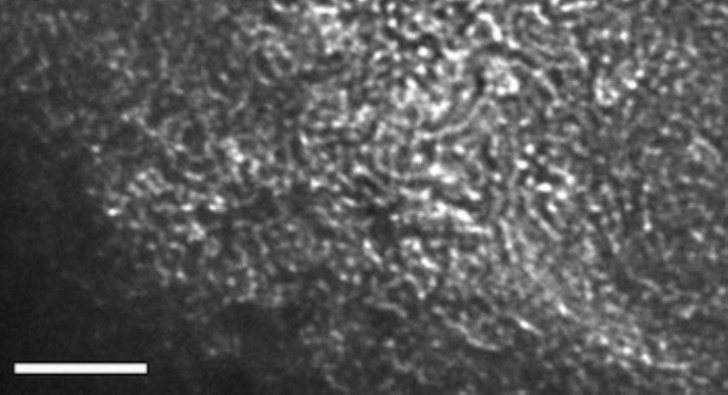

The Rice lab of chemist Andrew Barron has discovered that carbon-60 fullerenes (aka buckyballs) that have gone through the chemical process known as hydroxylation aggregate into pearl-like strings as they bind to and separate metals – some better than others – from solutions. Potential uses of the process include the environmentally friendly removal of metals from acid mining drainage fluids, a waste product of the coal industry, as well as from fluids used for hydraulic fracturing in oil and gas production.

Barron said the treated buckyballs handled metals with different charges in unexpected ways, which may make it possible to pull specific metals from complex fluids while ignoring others.

The study led by Rice undergraduate Jessica Heimann appeared in the Royal Society of Chemistry journal Dalton Transactions.

Previous research in Barron’s lab had shown that hydroxylated fullerenes (known as fullerenols) combined with iron ions to form an insoluble polymer. Heimann and colleagues conducted a series of experiments to explore the relative binding ability of fullerenols to a range of metals.

“It’s all very well to say I can take metals out of water, but for more complex fluids, the problem is to take out the ones you actually want,” Barron said. “Acid mining waste, for example, has large amounts of iron and aluminum and small amounts of nickel and zinc and copper, the ones you want. To be frank, iron and aluminum are not the worst metals to have in your water, because they’re in natural water, anyway.

“So our goal was to see if there is a preference between different types of metal, and we found one. Then the question was: Why?”

The answer was in the ions. An atom or molecule with more or fewer electrons than protons is an ion, with a positive or negative charge. All the metals the Rice lab tested were positive, with either 2-plus or 3-plus charges.

“Normally, the bigger the metal, the better it separates,” Barron said, but experiments proved otherwise. Two-plus metals with a smaller ionic radius bound better than larger ones. (Of those, zinc bound most tightly.) But for 3-plus ions, large worked better than small.

“That’s really weird,” Barron said. “The fact that there are diametrically opposite trends for metals with a 2-plus charge and metals with a 3-plus charge makes this interesting. The result is we should be able to preferentially separate out the metals we want.”

The experiments found that fullerenols combined with a dozen metals, turning them into solid cross-linked polymers. In order of effectiveness and starting with the best, the metals were zinc, cobalt, manganese, nickel, lanthanum, neodymium, cadmium, copper, silver, calcium, iron and aluminum.

The “pearl” reference isn’t far from literal, as one inspiration for the paper was the fact that metal ions are cross-linking agents for proteins that give certain marine mussels an amazing ability to adhere to wet rocks.

Barron said fullerenols act as chelate agents, which determine how ions and molecules bind with metal ions. Experiments with various metals showed the fullerenols bound with them in less than a minute, after which the combined solids could be filtered out.

Image: A transmission electron microscope image shows the aggregated "strings of pearls" that form when hydroxylated carbon-60 molecules crosslink with metals – in this case, iron and nickel – in a solution. The research suggests it may be possible to use the technique to remove specific metal molecules from solutions. The scale bar is 50 nanometers.

Image Source: The Barron Research Group

Source: Rice University